Can the weight of history shape a person’s mental health? For countless individuals born into India’s marginalized castes, the answer is a clear and painful yes. The caste system, built over centuries of religious and social control, has caused far more than just material deprivation. It has created a deep and often silent crisis of psychological suffering, passed down from one generation to the next like a wound that refuses to heal.

This trauma often remains unseen. It hides in the anxiety of stepping into a classroom and feeling like you do not belong. It shows up in the shame children are taught to feel about their surname, their skin tone, or their village. It lives in the silence of families too afraid to speak about what was done to them or what still happens today. Caste-based discrimination does not just deny opportunities. It attacks the very core of dignity, safety, and self-worth.

Marginalized castes have long been labeled impure, untouchable, and subhuman. These are not just relics of the past. They are still present in everyday life, reinforced by institutions, social interactions, and even the internal voices that many from these communities carry within themselves. The trauma is not historical alone. It is ongoing and deeply embedded in the structures around us.

Despite its widespread impact, caste-based trauma is rarely recognized in mainstream discussions about mental health. Most mental health systems do not account for the weight of generational oppression. In India, mental health is often treated as a private issue rather than a reflection of systemic violence. For many Bahujans, including those from Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes, mental health struggles are tied directly to centuries of exclusion, discrimination, and injustice.

In this article, we explore how caste-based trauma continues to affect mental health today. We look at the unique psychological challenges faced by oppressed communities, including internalized casteism, imposter syndrome, depression, chronic anxiety, and social isolation. We also highlight stories of resilience, community healing, and cultural strength that offer hope for recovery and justice.

The Roots of Caste-Based Psychological Trauma

Caste-based trauma is not a modern development. It is the result of a deeply rooted system of social hierarchy that has shaped Indian society for more than two thousand years. Long before colonialism, the caste system — traditionally known as Jati — determined how people lived, worked, related to others, and viewed their own self-worth. The psychological wounds caused by this system are deep and long-lasting. They are shaped not only by discrimination in daily life but also by internalized beliefs that restrict one’s ability to dream, grow, or feel human.

Historical Foundations of the Caste System

The Varna System and the Birth of Social Hierarchy

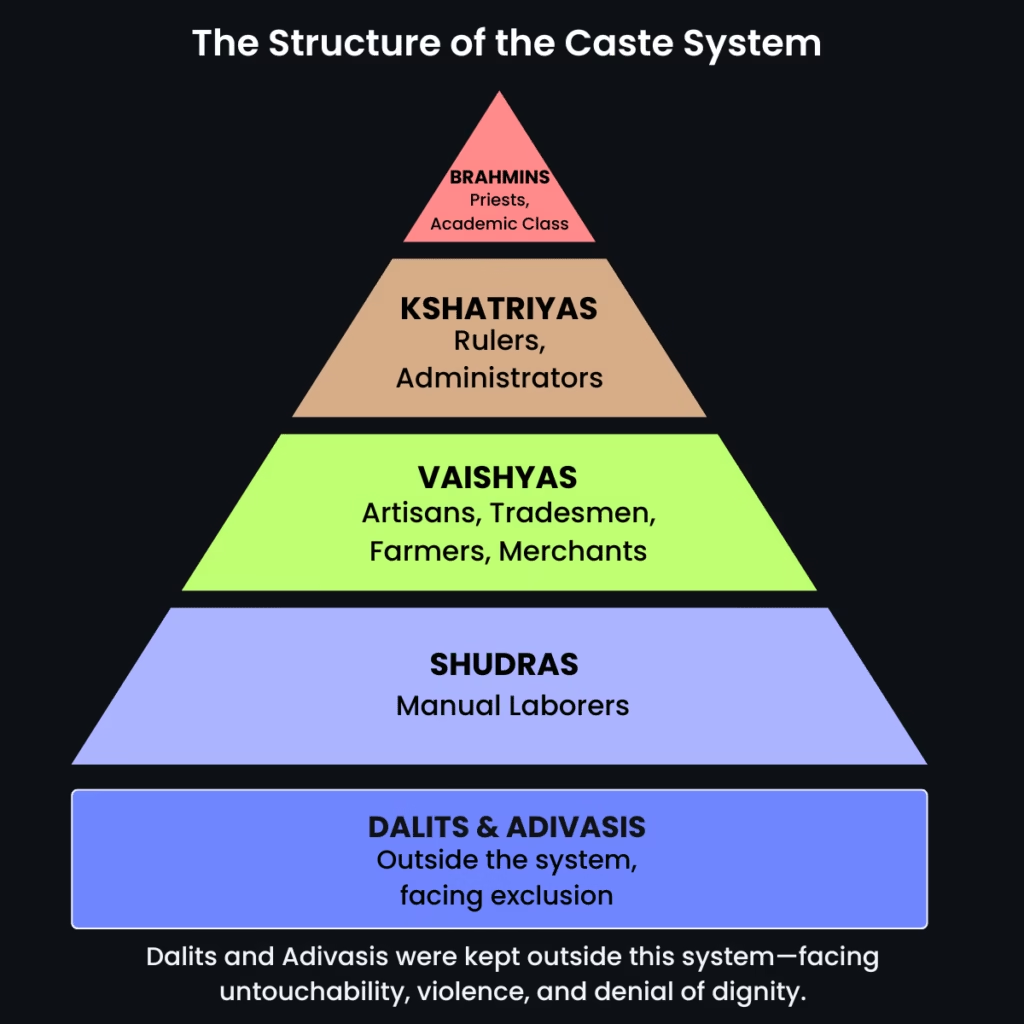

The origins of caste-based trauma lie in the religious and social frameworks that defined people’s lives. The Varna system, described in ancient Hindu texts, divided society into four major groups: Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (traders), and Shudras (servants). Outside this system were the Avarna — those who were denied any status at all and later came to be known as Untouchables, Ati-Shudras, or Dalits.

This structure was not flexible. A person’s caste was fixed at birth and could not be changed. It dictated where a person lived, whom they could marry, what work they were allowed to do, and even where they could walk or sit. This imposed identity was reinforced through religious belief, social practice, and cultural norms. It robbed people of their agency and labeled them with a lifelong tag of worth or worthlessness.

Codified Exclusion and Violence in Scriptures and Law

The caste system was not created by the British. It existed long before colonial rule and was justified through religious texts such as the Manusmriti. This ancient text is a collection of laws that laid down strict rules for caste-based roles and behaviors. It instructed that lower castes should serve the upper castes, remain uneducated, and face harsh punishment for disobedience. For example, it stated that a Shudra who dared to recite or even hear the sacred Vedas should have molten lead poured into his ears.

These ideas were not isolated or symbolic. They were institutionalized and practiced across generations. The idea that some people are born impure or inferior was embedded into spiritual and social life. The psychological damage caused by such messaging is severe. When people are told that their suffering is part of divine order, it is not only their body that is hurt, but also their mind and spirit.

This long history of systemic exclusion created a mental framework in which oppressed communities internalized shame, silence, and submission. The trauma was not always visible, but it was present in every interaction and every limitation imposed by society.

Structural Oppression and Identity Formation

How Caste Determines Self-Worth from Birth

In a caste-based society, identity is not something a person chooses. It is assigned at birth and constantly reinforced by families, schools, and community life. For those born into marginalized castes, this identity is tied to ideas of impurity, shame, and silence. Children learn early on that they are expected to be obedient, invisible, and never dream too big.

These early experiences shape how a person sees themselves. Many grow up feeling inferior or afraid to take up space. They learn to hide their roots and doubt their talents. The impact is long-lasting, often leading to self-hate, low self-esteem, and a belief that one is undeserving of respect or success.

This is psychological violence. It teaches children to question their worth before they even get a chance to prove it.

Education, Employment, and Social Status as Tools of Psychological Control

Caste-based oppression is not only cultural. It is also institutional. For centuries, oppressed castes were denied access to education and skilled jobs. This was not just to keep them economically dependent, but also to break their confidence and voice.

Even today, students and professionals from Bahujan communities face discrimination in classrooms, offices, and institutions. They are often seen as outsiders or “quota candidates,” regardless of their talent or effort. Their success is questioned, and their failures are exaggerated.

This constant surveillance and judgment create stress, anxiety, and emotional exhaustion. People are forced to work twice as hard just to be treated as equals. The fear of being rejected or humiliated adds to the burden, especially for those who are the first in their family to access education or formal employment.

Everyday Violence and Microaggressions

Verbal Abuse, Slurs, and Humiliation

Language plays a major role in enforcing caste-based oppression. Casteist slurs and insults are used in schools, streets, workplaces, and even on social media. These words are not just rude or disrespectful. They are meant to hurt, degrade, and remind people of their “place.”

For many from marginalized communities, public humiliation is not rare. It is part of daily life. Being mocked for one’s name, dialect, or background is a common experience. These verbal attacks cause shame, anger, and psychological pain that builds up over time.

The Mental Toll of Being Othered in Daily Life

To live in a casteist society is to be constantly aware of one’s identity. Whether it is walking into a room, applying for a job, or speaking up in class, many Bahujans feel the pressure to fit in, hide their background, or avoid conflict. This kind of emotional labor creates stress and fatigue.

The feeling of being watched or judged can lead to social anxiety, depression, and isolation. It becomes difficult to trust others or feel safe in public spaces. Many people learn to wear a mask, pretending, performing, and suppressing their real selves just to survive.

Social Exclusion, Tokenism, and Isolation in Schools and Workplaces

Even in places that claim to be inclusive, caste bias remains. In schools, Bahujan students are often excluded from peer groups, ignored by teachers, or treated with suspicion. In universities, their presence is questioned as a result of reservations, rather than merit.

In workplaces, they may be hired but not truly accepted. They are kept away from leadership roles or invited only to fulfill diversity quotas. This kind of tokenism isolates people further, as they are expected to represent their entire community without support or solidarity.

The lack of genuine inclusion leads to loneliness, helplessness, and disillusionment. Without safe spaces to share these experiences, many internalize the pain and blame themselves for the discrimination they face.

How Caste-Based Discrimination Affects Mental Health

Caste-based discrimination is not just a social and economic injustice; it is a psychological wound that affects millions, especially those from Bahujan, Dalit, Adivasi, and other marginalized communities. The mental health repercussions of casteism are often overlooked in mainstream discourse, despite being deeply damaging and pervasive. Here’s how caste oppression deeply impacts psychological well-being:

Internalized Casteism

Growing up in a society that repeatedly reinforces notions of caste hierarchy, many oppressed individuals internalize harmful beliefs. This manifests as:

Shame, Guilt, and Self-Blame: The constant exposure to messages, both overt and subtle, that label certain castes as “impure” or “lesser” leads to feelings of guilt and self-loathing. People begin to question their worth, often blaming themselves for the discrimination they face.

Believing One is “Less Than”: Cultural messaging embedded in textbooks, rituals, and everyday language promotes inferiority complexes. It erodes self-esteem and embeds the belief that they must work harder just to be seen as equal.

Chronic Stress and Anxiety

Living under the shadow of caste-based oppression is a constant source of stress. Many individuals experience:

Fear of Violence, Surveillance, or Exposure: From verbal abuse to physical violence, the threat is real. Marginalized students, professionals, and activists often conceal their caste identity out of fear. This breeds chronic anxiety.

Emotional Exhaustion and Hyper-vigilance: Always being alert and anticipating discrimination or humiliation creates a state of hyper-vigilance. This drains emotional resources and leads to burnout and long-term psychological distress.

Depression, Isolation, and Suicidality

When a society systematically denies dignity, it pushes individuals into despair.

Systemic Hopelessness: Being denied opportunities, ridiculed in institutions, or erased from narratives builds a sense of futility. Many feel there is no way out and no space to be heard.

Mental Health Crisis Among Bahujan Youth: Reports show a disturbing rise in suicides and depression among marginalized students in elite educational institutions. These are not isolated tragedies but symptoms of a larger social illness.

Imposter Syndrome and Social Anxiety

In classrooms, boardrooms, and beyond, caste-oppressed individuals face a dual battle: to succeed and to belong.

Struggling to Fit In: Many feel like outsiders, constantly battling the idea that they do not deserve their place in academic or professional spaces. The burden of representation becomes heavy.

Double Burden: There is the pressure to prove one’s competence while simultaneously concealing one’s caste identity to avoid bias. This double consciousness fuels social anxiety, self-doubt, and mental fatigue.

Caste-based discrimination is not a thing of the past; it is an ongoing trauma that shapes the mental health of millions. Addressing this requires more than policy changes or representation. It needs an empathetic, intersectional mental health movement that listens to Bahujan voices, validates their struggles, and creates safe spaces for healing and resistance. True mental health justice is not possible without caste annihilation.

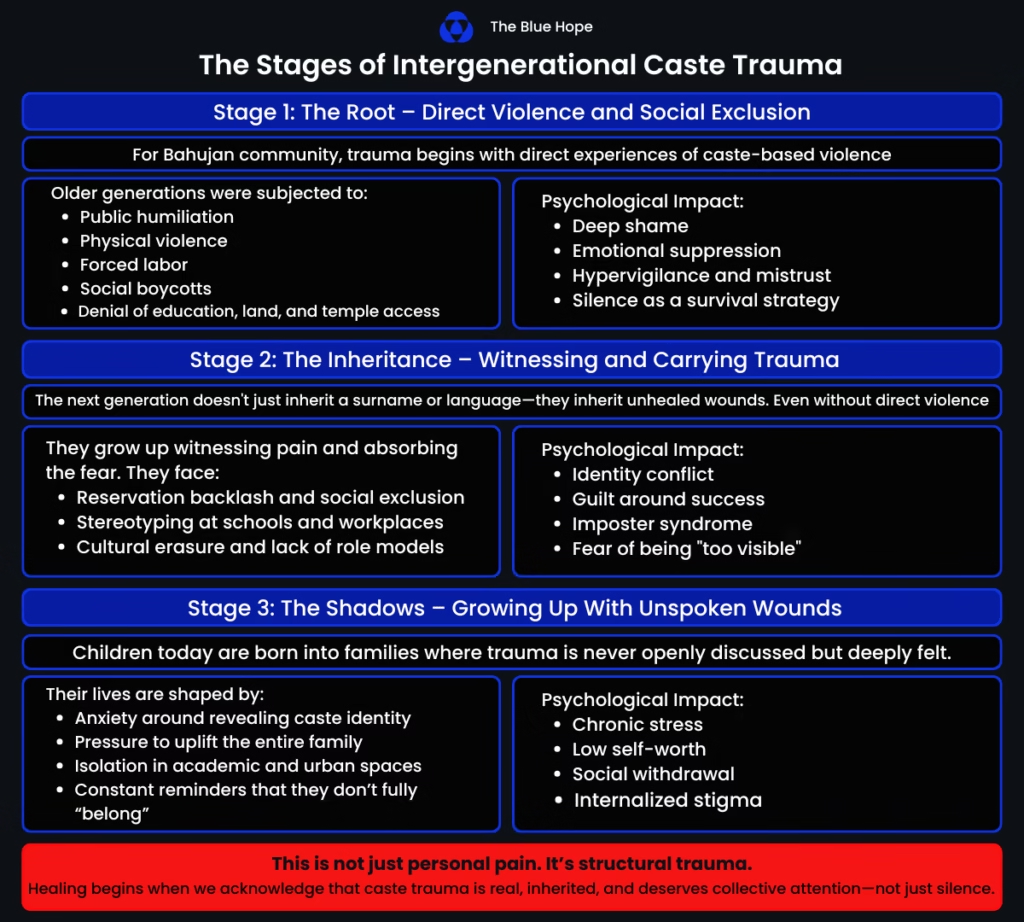

Intergenerational Trauma in Bahujan Communities

Intergenerational trauma refers to the inherited emotional and psychological wounds passed from one generation to the next. In Bahujan communities, which include Dalits, Adivasis, OBCs, and other historically oppressed caste groups in India, this trauma is both deeply personal and profoundly collective. It is rooted in centuries of systemic violence, exclusion, and caste discrimination.

Origins and Expressions of Trauma

This trauma shows up as low self-worth, emotional suppression, hypervigilance, and other survival behaviors shaped by historical oppression. For Bahujan families, these patterns often come from caste-based violence, forced labor, social rejection, and institutional marginalization.

These experiences become collective memory. They are preserved in stories, songs, silences, and behaviors. A parent’s fear of authority or a family’s insistence on staying unnoticed reflect past injustices still alive today.

How Trauma Is Passed Down

Trauma is transmitted not only through words but also through behavior, parenting styles, and reactions to stress. Children may inherit fears and coping mechanisms shaped by a parent’s experiences of caste discrimination. They internalize burdens that are not originally their own.

Recent epigenetic research supports this idea. It shows that trauma can cause chemical changes in DNA that affect future generations. This means ancestral stress may make descendants more prone to anxiety, depression, and other mental health challenges. Trauma thus has a biological aspect as well.

Impact on Bahujan Youth

Pressures to Succeed and Uplift the Family

Young Bahujans often face the dual challenge of healing ancestral wounds while trying to break cycles of poverty and exclusion. The pressure to succeed, driven by family sacrifices and unmet dreams, can be overwhelming. This responsibility to uplift both family and community can lead to burnout, imposter syndrome, or feelings of isolation. Although the idea of upward mobility is powerful, it often overlooks the emotional strain on the individual.

Disconnect Between Self and Cultural Roots

Many Bahujan youth struggle to balance their cultural identity with the demands of modern education, work, and urban life. They often face internal conflicts between embracing their caste identity and fitting into dominant social norms. This disconnect can deepen trauma, leaving young people feeling separated from both their heritage and the wider society. The result is a fragmented sense of self, torn between pride and pain, belonging and exclusion.

Pathways to Healing: Addressing Caste-Based Trauma

For Bahujan communities in India, including Dalits, Adivasis, OBCs, and other historically oppressed caste groups, healing is both a personal and political journey. Generations of caste-based discrimination, violence, and exclusion have left deep emotional and psychological wounds. While the fight for justice and equality continues, creating space for emotional well-being and cultural healing is just as important. This article outlines meaningful strategies that speak to Bahujan lived experiences and offer pathways toward collective and individual mental health.

1. Culturally Rooted Healing Practices

The Power of Ambedkarite Spirituality and Resistance

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s vision for liberation extended beyond law and policy. It included a spiritual revolution that rejected caste hierarchy and affirmed human dignity. Many Bahujans find healing in embracing Ambedkarite Buddhism, which provides a sense of belonging, compassion, and resistance. This spirituality becomes a source of strength, helping individuals reclaim their worth and stand against everyday caste-based oppression.

Buddhism as a Path to Healing and Reclaiming Identity

For centuries, caste oppression worked not only to dehumanize Bahujans but also to erase their history and spiritual heritage. Dr. Ambedkar reminded us that before the imposition of caste, our ancestors walked the path of the Buddha. By returning to the Dhamma, Bahujans are not adopting something new but reclaiming what was once stolen. Saying “Buddham Saranam Gacchami” is more than a religious chant; it is an act of healing, resistance, and deep affirmation. Buddhism offers a mental, emotional, and spiritual refuge from the violence of caste. Through the Buddha’s teachings, which are centered on compassion, equality, and mindfulness, Bahujans can find tools to process trauma, rebuild self-worth, and live with dignity. This return to the Buddha’s path is a powerful reminder that our true identity was never defined by caste but by wisdom, resilience, and humanity.

Community Rituals, Songs, and Stories as Tools of Resilience

Bahujan communities have long used oral traditions, songs, and storytelling as ways to preserve memory and resist erasure. Protest songs like Bhim Geet, and the poetry of Sant Ravidas and Kabir, offer more than cultural expression. They are emotional lifelines. Sharing stories, singing together, and remembering collective struggles can help individuals feel seen, valued, and connected to a larger history of resistance.

2. Building Affirming Mental Health Spaces

Bahujan-led Counseling, Support Groups, and Online Spaces

Mental health services that are shaped by Bahujan voices can offer much-needed safety and cultural understanding. When therapists and facilitators come from similar caste backgrounds, it allows for deeper empathy and trust. Online platforms and peer-led support circles rooted in Ambedkarite values are creating much-needed mental health spaces that reflect the realities of caste-based trauma.

The Role of Safe Schools, Libraries, and Community Centers

Physical spaces that affirm Bahujan identities are essential. Schools that support inclusive curricula, libraries filled with anti-caste literature, and community centers that welcome marginalized youth all contribute to emotional well-being. These spaces allow individuals to imagine a future free from caste discrimination, while building self-esteem and resilience.

3. Personal Coping Strategies

Mindfulness and Grounding for Managing Anxiety

Mindfulness practices like deep breathing, grounding exercises, and body scans can be helpful tools for managing stress. For Bahujans, however, these tools take on deeper meaning when practiced with awareness of the caste-based realities they live through. Finding calm is not about ignoring oppression, but about restoring strength to continue resisting it.

Journaling, Art, and Storytelling for Emotional Expression

Creative expression provides an outlet for pain, hope, and reflection. Journaling helps process emotions and internal conflicts. Art and storytelling offer powerful ways to speak truth, reclaim identity, and release suppressed feelings. These acts are not just therapeutic—they are deeply political when they challenge dominant narratives.

Affirmations and Deconstructing Internalized Casteism

Many Bahujans grow up facing caste-based shame and humiliation, which often leads to internalized self-doubt. Healing involves actively unlearning those harmful beliefs. Affirmations like “My worth is not defined by caste,” or “I am powerful and capable,” help challenge those internalized messages. These daily practices of self-affirmation can be small but radical acts of defiance and healing.

4. Role of Allies and Mental Health Professionals

Listening Without Saviorism

Being an ally means offering support without centering oneself. True solidarity involves listening to Bahujan voices with humility and respect, without trying to take over or “save” anyone. Allies must be willing to follow rather than lead, and to learn without defensiveness.

Educating Oneself on Caste and Systemic Trauma

Mental health professionals, educators, and friends need to take the responsibility of learning about caste, not expecting Bahujans to explain everything. Reading anti-caste literature, learning from Bahujan scholars and activists, and understanding how systemic trauma operates are crucial steps in becoming truly supportive.

Creating Caste-Aware, Trauma-Informed Therapy Spaces

Mainstream therapy in India often lacks an understanding of caste and its psychological impact. Therapists need to create safe, inclusive spaces that acknowledge caste trauma and actively work against caste-based assumptions. A trauma-informed, caste-aware approach is essential for real healing.

For Bahujan communities, healing is an act of resistance. It is about reclaiming what caste oppression tried to erase: dignity, voice, and power. Whether through collective rituals, therapy, creative expression, or spiritual practice, the path to healing is deeply rooted in the affirmation of Bahujan identity and struggle. When we center culturally grounded mental health practices, we move closer to a world where Bahujan healing is not only possible, but inevitable.

Common Misconceptions About Caste-Based Trauma

Caste-based trauma deeply affects Bahujan communities in India, including Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), Other Backward Classes (OBC), and other historically oppressed groups. While mental health is gradually becoming part of public conversations, the specific trauma caused by caste-based discrimination is still poorly understood. These common misconceptions often stand in the way of meaningful healing and justice:

Misconception 1: “Caste discrimination no longer exists”

Some people believe that caste is a thing of the past because of legal protections. In reality, caste discrimination continues in many forms today. From being denied housing in urban areas to subtle exclusion in classrooms and overt violence in villages, caste remains a daily barrier for millions. For Bahujan individuals, this ongoing discrimination adds to generations of historical trauma. Legal reforms are necessary, but they have not erased social realities.

Misconception 2: “Economic success erases caste trauma”

It is often assumed that education, employment, and financial success can protect someone from caste-based harm. While these things can offer some relief, they do not remove the psychological burden. Many successful individuals from marginalized castes still face discrimination in elite institutions, professional spaces, and social gatherings. Trauma is not only linked to poverty. It also comes from being treated as inferior, excluded, or invisible, no matter how high one climbs.

Misconception 3: “Mental health issues are just personal problems”

In many Indian households, mental health is seen as a personal or family matter. But for Bahujan people, much of the distress comes from systemic oppression and generational injustice. Caste-based trauma is not just a private issue. It is shaped by centuries of violence, humiliation, and exclusion. Healing must include personal care, but it also requires collective awareness and structural change.

Misconception 4: “Talking about caste creates division”

Many argue that bringing up caste only creates tension. This idea is often used to silence marginalized voices. But talking about caste does not create division; it reveals the inequality that already exists. Ignoring caste will not make discrimination go away. As one activist said, “We can’t heal what we refuse to name.” Acknowledging trauma is the first step toward healing, justice, and true social harmony.

Conclusion: Toward Healing and Justice

Caste-based trauma is real. It is rooted in centuries of oppression and continues to shape the mental health of millions today. The psychological wounds caused by generations of discrimination do not simply fade. They require recognition, care, and consistent efforts to heal.

Understanding the historical roots of caste and its ongoing impact is not just about looking back. It is about confronting how the past continues to influence the present. It means reshaping unjust systems, expanding access to mental health care, and creating communities where every person’s dignity is respected and upheld.

Healing from caste-based trauma is both a personal and collective journey. It calls for empathy, education, and action. To build a more just and compassionate society, we must actively challenge caste-based discrimination and replace exclusion with belonging, shame with pride, and silence with voice.

As Dr. B. R. Ambedkar said, “The history of India is nothing but a history of a mortal conflict between Buddhism and Brahmanism.” That conflict still exists today in the struggle between equality and hierarchy, between trauma and healing, and between oppression and liberation.

The path forward asks us to care for ourselves and stand with each other. When we understand caste-based trauma and work together to overcome it, we help create a world where mental health is not limited by birth, but supported by justice, freedom, and humanity.