Have you ever felt emotionally exhausted just for being yourself? For being treated unfairly, not because of what you did, but because of where you come from?”

For millions in India, this question is not hypothetical; it’s a lived reality. The caste system, a deeply entrenched social hierarchy, continues to shape lives in ways that are both visible and invisible. While its impact on education, employment, and social mobility is often discussed, its toll on mental health remains underexplored. Yet, mental health is not just a personal matter; it is profoundly shaped by social structures like caste. Understanding this connection is essential for healing and creating a more just society.

This article explores the historical roots of caste-based trauma, the emotional toll it takes on individuals and communities especially Bahujan communities and the pathways to collective healing.

Historical Roots of Caste-Based Trauma

The caste system, rooted in Hindu tradition but extending beyond it, divides people into rigid hierarchical groups based on birth. Historically, those at the bottom of this hierarchy Dalits, Adivasis, and other marginalized communities collectively referred to as Bahujans have faced systemic exclusion and dehumanization. Denied access to education, land ownership, and even basic human dignity, they were forced into degrading occupations like manual scavenging.

This exclusion was not just economic or social; it was psychological. Being told for generations that you are “less than” others leaves deep scars. These scars are not just historical, they are carried forward through intergenerational trauma. Today, Bahujan communities continue to face discrimination in schools, workplaces, healthcare systems, and even within their own neighborhoods.

The Emotional Toll of Caste Oppression

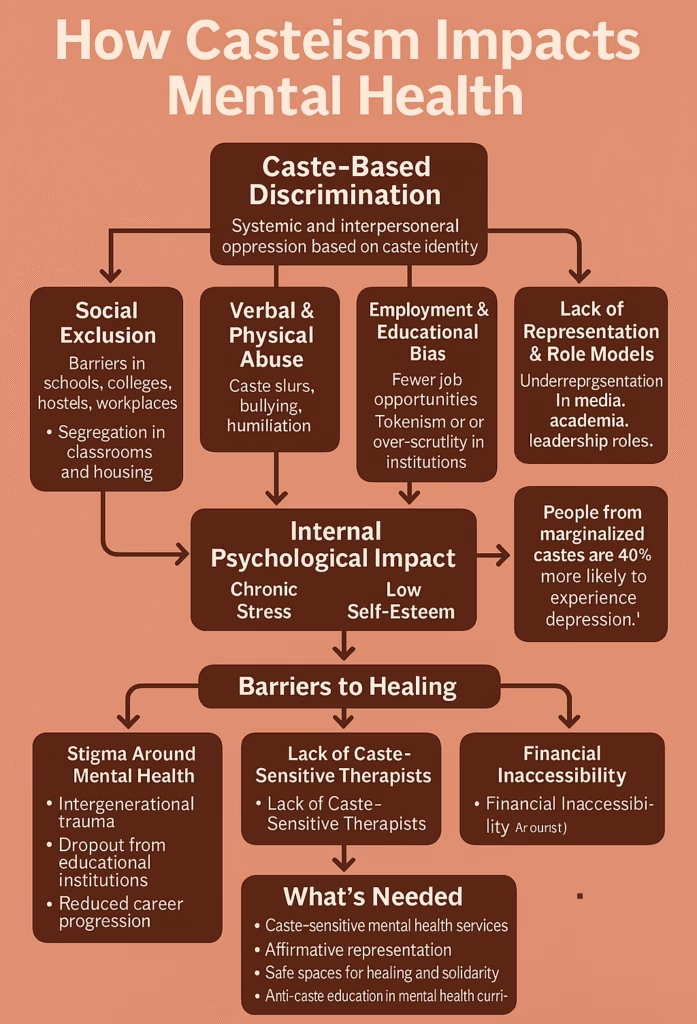

Caste-based oppression creates a unique set of mental health challenges that go beyond individual experiences. The constant reminder of one’s “place” in society can lead to chronic stress, low self-esteem, and emotional exhaustion.

Daily Discrimination and Chronic Stress

Imagine walking into a classroom or workplace and feeling like people are already judging you, not because of your skills or how smart you are, but because of your caste background. This is a common experience for many Bahujans who enter spaces where most people come from so-called upper-caste communities.

Sometimes the discrimination is obvious like being left out of group activities, ignored in meetings, or spoken to with disrespect. Other times, it’s more subtle. People might make comments that seem small but carry a lot of weight, these are called microaggressions. For example, someone might say, “You must have gotten in through reservation,” as if your hard work doesn’t count.

Facing this kind of treatment again and again can take a serious toll on mental health. Many Bahujans in these spaces start to feel anxious, stressed, or even depressed. Studies have found that people from marginalized castes experience much higher levels of mental health struggles like depression and anxiety—compared to their upper-caste peers.

These feelings are not just personal—they are the result of living in a system that constantly makes you feel unwelcome or not good enough. Understanding this is the first step toward healing and creating more inclusive and respectful spaces.

Low Self-Worth

Generations of being told you are “inferior” can erode self-confidence. Many Bahujans internalize these messages, leading to feelings of shame and self-doubt. For students from marginalized communities, this often manifests as a fear of not belonging or being “good enough,” even when they excel academically or professionally.

Isolation and Hypervisibility

In places like top universities or big corporate offices, there are often very few Bahujan people. Because of this, Bahujans who enter these spaces can feel very alone. They might not see anyone else from a similar background, which can make them feel like they don’t belong.

At the same time, they are often treated differently. People might call them a “quota candidate”—a hurtful term used to suggest that they got in only because of caste-based reservations, not because of their own talent or hard work. This unfair label can be very painful and embarrassing.

This kind of treatment is part of something called hypervisibility—when someone stands out too much in a negative way. Instead of being seen as just another student or coworker, Bahujans are often seen only as a representative of their entire community.

So, they carry two heavy burdens at once: feeling invisible and alone, but also being unfairly watched and judged. This double pressure can make them feel emotionally tired, mentally stressed, and disconnected from the people around them.

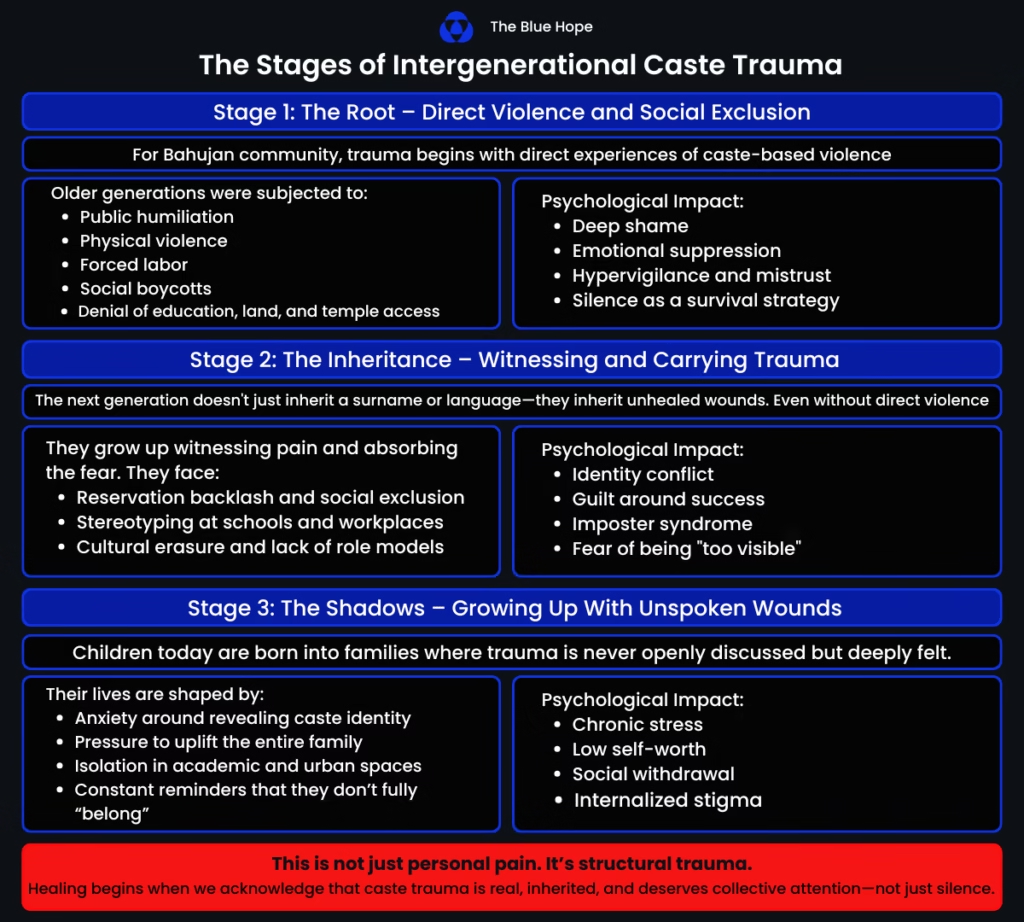

Intergenerational Trauma

Caste-based trauma doesn’t just affect one person or one generation—it gets passed down from parents to children, and even to grandchildren. This is called intergenerational trauma.

In many Bahujan families, children grow up seeing their parents or elders being treated unfairly. They may witness them facing insults, being excluded, or struggling just to get basic respect and opportunities. Even if no one talks about it openly, these painful experiences leave deep emotional scars.

Over time, children start to carry this pain too. It shapes how they see the world, how safe they feel, and how confident they are. This kind of trauma can affect a child’s mental health from a very young age, even if they themselves haven’t faced direct discrimination yet. It stays in the body and mind, influencing how people grow, think, and relate to others.

Understanding intergenerational trauma is important, because healing doesn’t just mean helping one person—it means breaking the cycle for future generations too.

The Stigma Around Mental Health in Marginalized Communities

In many Bahujan households, mental health is rarely discussed—not because it isn’t important but because survival takes precedence. When you’re fighting for basic needs like food, shelter, and education, emotional well-being often feels like a luxury.

Survival Over Self-Care

For many Bahujan families dealing with poverty or facing social exclusion, mental health often takes a backseat. When the main focus is on meeting basic needs like food, education, or work, things like therapy or self-care can feel like a luxury.

Even when someone wants help, it’s not always easy to find. Therapy can be expensive, and many mental health professionals may not understand the realities of caste or the struggles of marginalized communities. This makes it even harder for Bahujans to get the kind of support they truly need.

Shame and Guilt

In many communities, talking about mental health is seen as a weakness. Bahujans who are struggling often feel ashamed to ask for help, worried that others will judge them or say they’re just being too sensitive.

On top of that, many feel guilty for focusing on their own feelings when their families are facing bigger problems—like poverty, discrimination, or survival. It can feel selfish to think about your mental health when others around you are suffering. But this guilt only adds to the emotional burden, making it even harder to heal.

Recognizing the Psychological Effects

Understanding the mental toll of caste-based oppression is the first step toward healing. Many Bahujans live under constant pressure due to systemic exclusion, which affects their emotional and psychological well-being in deep and lasting ways:

- Chronic Stress: Daily encounters with discrimination, whether overt or subtle, can overload the body’s stress response system. Over time, high cortisol levels contribute to fatigue, sleep disturbances, weakened immunity, and emotional exhaustion.

- Depression and Anxiety: When people are repeatedly denied opportunities or made to feel inferior, it can lead to persistent sadness, fear, or a sense of helplessness. These emotions often develop into clinical depression or anxiety disorders, especially when support systems are lacking.

- Internalized Casteism: Many Bahujans begin to absorb society’s negative messages, leading to self-blame or shame—especially around policies like reservations. Instead of seeing these tools as rightful support, some may feel undeserving, which erodes confidence and self-worth.

- Generational Impact: The trauma doesn’t end with one generation. Children growing up in marginalized communities often witness their parents’ struggles and experience the same discriminatory environments. This can lower their self-esteem and limit how far they believe they can go in life.

Pathways to Healing

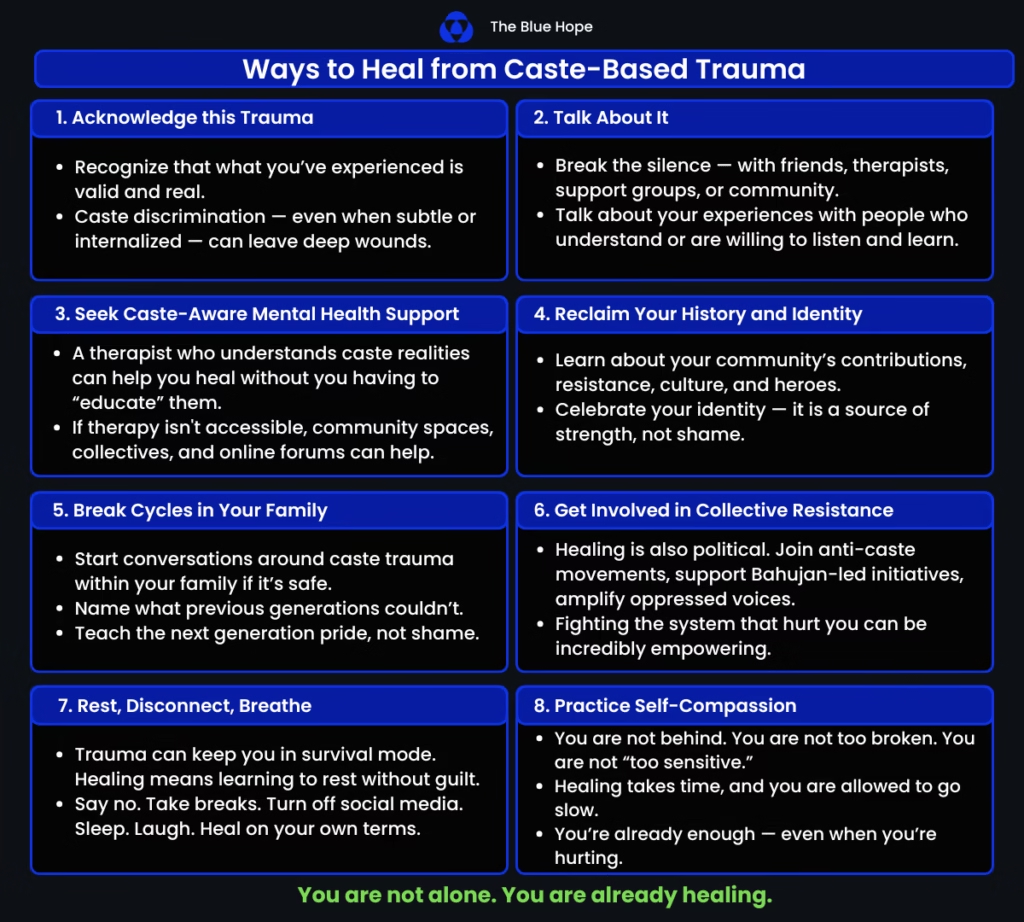

Healing from caste-based trauma is a complex process, requiring both personal effort and collective action. It involves addressing the mental and emotional scars left by systemic injustice, while also creating spaces for growth, empowerment, and community support:

1. Naming the Oppression

The first step in healing is recognizing that the pain is not a result of personal inadequacy, but of systemic caste-based oppression. By understanding that casteism is a societal issue, individuals can begin to reclaim their dignity and stop internalizing shame. This shift in perspective is liberating and helps break the chains of self-blame, allowing individuals to start healing with clarity and purpose.

2. Building Supportive Networks

Healing thrives in a safe and understanding environment. Supportive networks whether online forums, community groups, or peer circles offer a space to share experiences without the fear of judgment or retribution. Platforms like The Blue Dawn connect Bahujans with therapists who not only understand the struggles of caste-based trauma but are also trained to provide culturally sensitive care. Being able to speak openly and connect with others who share similar experiences fosters a sense of solidarity and resilience.

3. Accessing Mental Health Resources

While access to therapy can be limited due to financial or geographical barriers, there are increasingly accessible options for mental health support. Many NGOs and online platforms offer free or low-cost counseling, and some specialize in supporting marginalized communities. Additionally, practices like journaling, mindfulness, and art therapy allow individuals to process their feelings creatively and reflectively. Storytelling is another powerful tool, as sharing personal experiences can be a form of emotional release and a way to reclaim one’s narrative.

4. Setting Boundaries

Protecting one’s mental health is essential in the process of healing. This often involves setting clear boundaries with individuals or environments that perpetuate casteist attitudes or normalize discrimination. This might include limiting interactions with people who hold prejudiced views or creating distance from spaces where casteism is tolerated. It’s also important to advocate for policies that protect against caste-based discrimination in workplaces, educational institutions, and communities.

5. Representation Matters

Seeing positive representations of Bahujans in various fields be it media, politics, academia, or mental health professions—can provide vital role models for future generations. Representation helps foster a sense of pride, hope, and possibility, encouraging young Bahujans to envision success and leadership in areas where they’ve traditionally been excluded. It shows them that they, too, can break barriers and excel in any field.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. How does caste-based discrimination affect mental health?

A: Caste-based discrimination leads to chronic stress, low self-esteem, and anxiety. Marginalized communities face daily exclusion, which can contribute to depression and feelings of hopelessness.

Q2. What is internalized casteism, and how does it harm mental health?

A: Internalized casteism occurs when individuals from marginalized castes believe the negative stereotypes about their community. This leads to feelings of guilt, shame, and self-doubt, affecting their confidence and mental well-being.

Q3. Why is mental health not prioritized in Bahujan communities?

A: In Bahujan communities, the focus is often on survival—securing food, education, and shelter—making mental health seem secondary. Additionally, there is social stigma around seeking help, as it may be seen as a weakness.

Q4. How can caste-based trauma be passed down through generations?

A: Generations of caste-based exclusion create emotional scars that get passed down. Children inherit the trauma of their parents’ struggles, leading to low self-worth and limited aspirations from a young age.

Q5. What are the biggest barriers to accessing mental health care in marginalized communities?

A: Barriers include financial constraints, lack of culturally sensitive professionals, and the stigma around mental health. Many marginalized individuals struggle to find affordable, appropriate care.

Q6. How can representation in media and leadership help mental health recovery?

A: Seeing Bahujan leaders in media, politics, and mental health fields provides role models and hope. Representation empowers individuals, showing that success and mental well-being are possible despite systemic oppression.

A Call for Collective Action

Healing from caste-based trauma isn’t just an individual journey—it’s a collective fight for justice. Promoting mental health education in Bahujan communities can help break the stigma around seeking help. Encouraging more Bahujans to enter the mental health field ensures culturally informed care becomes more accessible.

Technology also offers new possibilities: online platforms connecting individuals with anti-caste therapists or creating virtual safe spaces where stories can be shared freely.

Conclusion: Healing as Resistance

Healing is not a luxury—it is your right. Mental health is deeply connected to justice, dignity, and identity. By addressing the psychological toll of caste oppression, we take one step closer to dismantling its hold on our lives.

To every reader from marginalized communities: Your pain matters—but so does your joy. Your story is part of a larger collective fight for equality. And in reclaiming your mental well-being, you reclaim your power.

Let us remember: healing isn’t just about surviving—it’s about thriving together as we build a world where no one has to feel less than human simply because of where they come from.